I would never want to join a club that would have me as a member,” said comedian Groucho Marx. The increasingly congested private equity sector should consider taking a similar approach.

The private equity clique is becoming less gilded. Last week, President Donald Trump opened the door for US retirement saving plans known as 401k to invest in alternative assets such as corporate buyout funds and cryptocurrencies.

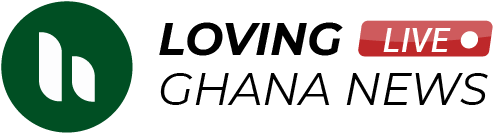

At the same time, big private capital managers have been expanding their retail products — known as “evergreen” funds — which had initially been narrowly targeted at high net worth individuals and now are becoming even more accessible. According to PitchBook, there are about 400 total US evergreen private capital funds that collectively manage $400bn. A couple of dozen now launch across private capital strategies yearly.

One question now is how managers can navigate capital from different sources that have different expectations for returns and liquidity. Evergreen funds constantly raise money from investors and allow periodic redemptions. Institutional “drawdown vehicles” have seven to 10 year lifespans, with most of the cash returned at the end.

The Financial Times reported last week that KKR had adjusted its terms with traditional limited partners such as pensions and endowments to allow greater participation from retail funds into its buyout vehicles. Last year, a KKR executive claimed that these small-time investors were getting a big-time deal: “You’re not getting the leftovers; you’re sitting side by side with our institutional clients.”

It should be no surprise that those already past the velvet rope are starting to feel a little unloved with the arrival of newcomers. Still, even for institutional investors there is a VIP section that provides special treatment. The biggest players like sovereign wealth funds often ink so-called “side letters”, which get them better terms on fees and other economic arrangements.

Sponsors are accustomed to managing such tensions and complexity, usually by adding more financial engineering. Continuation vehicles, NAV loans and secondary trading in limited partner stakes can all help with easing new investors in and out of a fund.

Retail and institutional capital should be aligned in one respect: scepticism of private equity sponsors. Even at cheaper evergreen funds, management and performance fees are typically 1 to 2 points and 10 to 15 points, respectively.

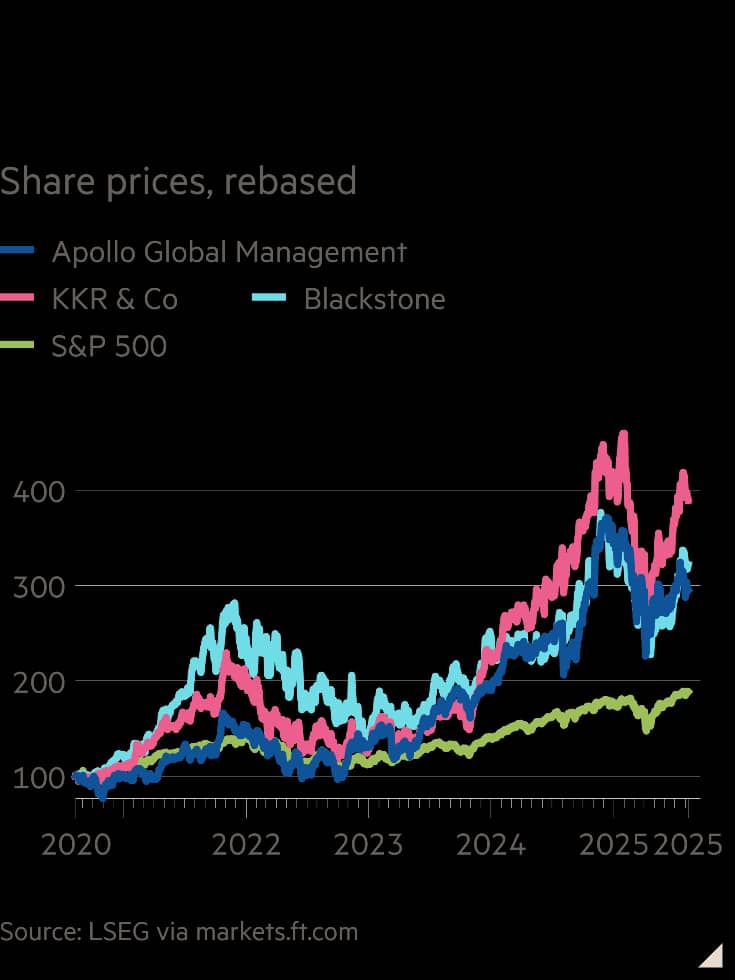

What’s more, private equity managers, especially listed ones, are motivated to raise more and more money across all types of capital pools in order to maximise their management fees. That may not be ideal for investors: a mass of money chasing opportunities can lower deal returns. Historically, private equity funds sought 25 per cent returns but are now willing to accept 15 to 20 per cent.

Private equity has done a good job so far of convincing all kinds of investors that their product is a necessary component of balanced portfolios. But getting people to remain members of a rapidly expanding club is the next difficult task.

Source:https://www.ft.com/