The next major front in global geopolitics may not open in the Taiwan Strait, but in the oil fields and shipping lanes that power the world economy. With Venezuela drifting back under U.S. influence following the removal of Nicolás Maduro, and Iran increasingly framed as Washington’s next pressure point, energy is quietly becoming the central lever in great power competition.

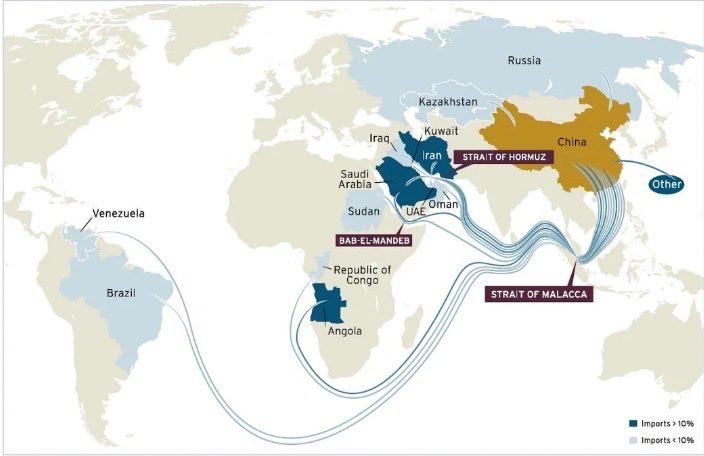

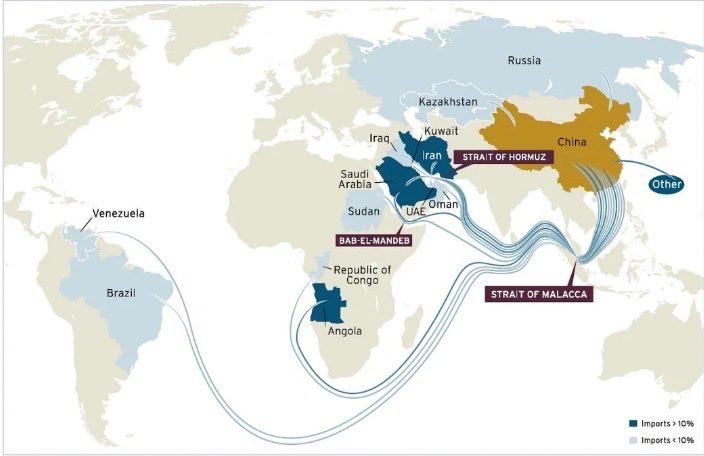

For years, China has benefited from discounted crude imports from both Venezuela and Iran, supplies that helped cushion its manufacturing base, control inflation, and sustain economic growth amid global volatility. If those channels are disrupted or redirected under governments aligned with Washington, Beijing’s access to cheap energy would narrow significantly, even without a single shot fired over Taiwan.

Such a shift would give the United States a form of strategic leverage that is harder to counter than military deterrence. With much of OPEC+ maintaining pragmatic or cooperative ties with Washington, China could find itself increasingly dependent on Russia for energy supplies. That dependence, while stabilising in the short term, would expose Beijing to pricing pressure, logistical constraints, and geopolitical risk, particularly if Western sanctions regimes tighten further.

The consequences would extend well beyond energy prices. Higher oil costs would feed directly into China’s industrial sector, raising production expenses, squeezing export competitiveness, and adding inflationary pressure at home. Supply chains across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, many of them deeply linked to Chinese demand, would feel second order shocks, potentially slowing growth in emerging markets.

Control over energy routes would also matter as much as control over supply. Choke points such as the Strait of Malacca, the Red Sea, and key Atlantic shipping corridors would gain renewed strategic importance, turning maritime security into an economic pressure tool rather than a purely military concern.

What is often overlooked is that this strategy does not require a crisis over Taiwan to take effect. Even in the absence of conflict, reduced access to discounted oil could gradually erode China’s economic momentum, narrowing Beijing’s strategic options over time. Energy security, not semiconductors alone, may prove to be the decisive constraint.

The broader implication is clear: the balance of global power may increasingly hinge on who controls energy flows, pricing, and access, not just who fields the largest armies.

In this contest, oil is not merely a commodity, but a geopolitical instrument shaping the choices of nations long before conflict becomes inevitable.